Whatcom County Dairy Future

UA

Unknown Author

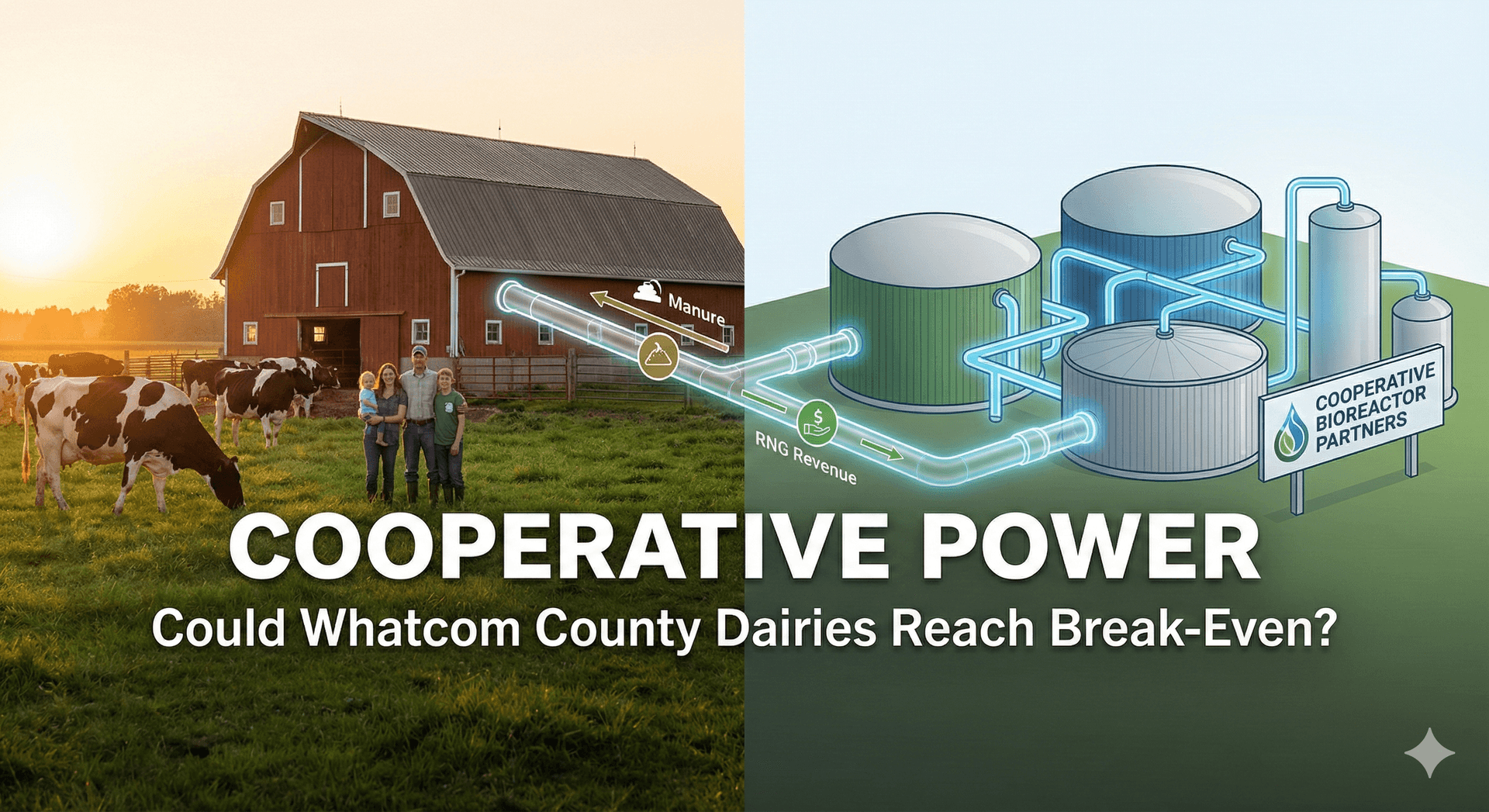

Could Whatcom County Dairies Reach Break-Even? Our Research Says Maybe

Preliminary findings suggest a path forward for small dairy farms through cooperative bioreactor technology

Running a small dairy farm has never been easy, but the economics have become increasingly brutal. Many family operations now survive on razor-thin margins or operate at outright losses, with costs steadily climbing while milk prices remain stubbornly flat. Here in the Pacific Northwest, we've been asking a question: what if the answer to dairy farm economics has been sitting in the lagoon the whole time?

At Resonetta, we've been researching how cooperative bioreactor technology could transform the economics of small dairy operations in Whatcom County, Washington. Our preliminary findings are promising enough that we wanted to share them with the community—while being clear that there's still a lot of validation work ahead.

The Problem: Small Farms, Big Economics

Whatcom County is home to approximately 70 dairy farms, most averaging around 550 cows. These operations are too small to justify the capital investment of standalone anaerobic digesters, which typically need several thousand cows to make economic sense. That leaves farmers managing manure the traditional way—spreading it on fields, paying for hauling, and treating what should be a resource as a cost burden.

Meanwhile, larger operations and corporate farms have been able to invest in digester technology, capturing methane and generating revenue from renewable natural gas. The economics have left small family farms behind.

The Opportunity: Cooperative Power

Our research centers on a cooperative model where multiple farms pool their manure at a central processing facility. When you combine the manure from 10-15 farms representing 15,000 or more cows, the economics shift dramatically.

The primary value driver is renewable natural gas (RNG) production for California's Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) credits. Based on current market conditions and credit values, our preliminary analysis suggests potential revenue in the range of $2,800 to $3,000 per cow annually—far exceeding what individual farms could generate through electricity production or other alternatives.

For a 550-cow operation, that could translate to roughly $1.5 to $1.6 million in annual revenue from what was previously a liability.

Getting Closer to Break-Even

But the RNG revenue is only part of the picture. One underappreciated aspect of digester operations is the digestate—the material left over after anaerobic digestion. This nutrient-rich material can be processed into fiber bedding and fertilizer, reducing input costs for participating farms.

We've been particularly interested in feed cost reduction for non-milking cows (dry cows and heifers). Feed represents 40-60% of total dairy production costs, and any reduction here has an outsized impact on the bottom line. With homegrown corn silage enabled by digestate-derived fertilizers, some operations could see significant savings compared to purchasing feed at market prices.

When you combine the RNG revenue with reduced feed and input costs, our models suggest small dairy operations could approach break-even on their cash operating costs—a dramatic shift from the current economics where many farms barely survive or operate at losses.

The Premium Milk Path

There's another avenue we're exploring: animal welfare certification. Farms operating within a cooperative structure have an opportunity to standardize practices and pursue premium certifications that command higher milk prices. For operations already implementing the infrastructure changes that cooperative membership would require, adding welfare certification becomes more feasible.

This creates a potential "stack" of revenue improvements: RNG credits plus reduced input costs plus premium milk pricing. Each component contributes to making small dairy farming economically viable again.

A Word of Caution: This Research is Preliminary

We want to be absolutely clear: these findings are early-stage. Our economic models are based on current LCFS credit values, which fluctuate with market conditions. The regulatory landscape is evolving, with significant changes coming to California's program by 2030. Infrastructure costs, transport logistics, and cooperative formation challenges all need more validation.

We haven't built a working cooperative yet. We haven't processed our first ton of manure. What we have is research, models, and a thesis we believe is worth pursuing.

There's also the matter of timing. California's LCFS rules are tightening, with new requirements for physical deliverability coming into effect January 1, 2030. Projects that become operational before then may be grandfathered into more favorable credit structures, which creates both urgency and risk.

Building Understanding: Our Simulator and Educational Tools

Part of our work at Resonetta has been developing educational tools to help farmers, investors, and community members understand the technology and economics involved. We've built an interactive simulator that walks through the entire process—from manure collection through RNG production to LCFS credit generation.

The simulator isn't just a demonstration; it's a learning tool that helps people understand the variables that affect project economics. What happens when LCFS credit prices drop 20%? How does transport distance affect viability? What's the minimum cooperative size that makes sense? These are questions the simulator helps explore.

We've also developed interactive games covering pipeline flow requirements, co-digestion optimization, and cooperative formation mechanics. Our goal is to make complex technical and regulatory concepts accessible to anyone considering whether this path makes sense for their operation.

Community Science: Micro-Processors and Lab Experiments

Perhaps the most exciting part of our work is what we're calling our community micro-processor network. We're enabling community members to contribute to our research by running small-scale experiments in home laboratory setups.

These garage-scale bioreactors help us understand system principles, test co-digestion ratios, and validate our models with real-world data. It's citizen science applied to agricultural technology—and it's generating insights that would be impossible for a small startup to develop alone.

If you're interested in contributing to this research, we'd love to hear from you.

What's Next: Hopefully, a Big Project

We're hopeful that Whatcom County will become Resonetta's flagship cooperative project. The region has the right characteristics: a concentration of small farms with similar needs, existing agricultural infrastructure, and a community with deep dairy farming roots.

Our next steps involve more validation work, conversations with farmers about their specific challenges and concerns, and development of the regulatory and business frameworks needed to make a cooperative function. We're approaching this by listening first—understanding what farmers actually need before proposing solutions.

The dairy industry is facing existential challenges. Climate regulations, shifting consumer preferences, and brutal economics are squeezing family operations from every direction. We believe cooperative bioreactor technology offers a path forward—not a silver bullet, but a meaningful improvement that could help keep small farms viable for another generation.

If you're a Whatcom County dairy farmer curious about what cooperative membership might look like for your operation, we'd welcome the conversation. And if you're a researcher, investor, or agricultural organization interested in this space, we're actively building partnerships.

The math is promising. Now comes the hard work of proving it out.

Resonetta is developing manure cooperative bioreactor technology to transform dairy manure from a cost burden into a profitable revenue stream. Our research is ongoing, and we're committed to transparency about both the opportunities and challenges ahead.